I’m currently organizing my notes for a novel based on the unfortunate life of my fourth great-uncle Fernando C. Kegley (1846–1925). To that end, here’s a little goody I’ve been meaning to release into the wild for some time. This is the will of Dr. Christian Lewis Kegley, Fernando’s father (and my fourth great-grandfather), who was the first of my line of Kegleys to move from Wythe County, Virginia, to Johnson County, Indiana, in 1829. I photographed this will in late 2021 during a visit to the Genealogy Library at the Johnson County Museum of History in Franklin, Indiana, but I’ve only just got around to transcribing it. The complete transcript of the will follows my commentary, so you can scroll down for the real thing if desired.

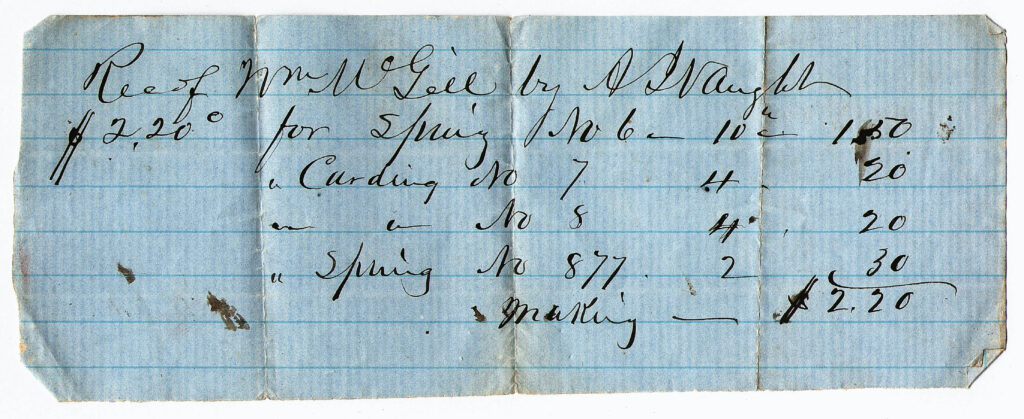

Christian Kegley’s will stands out from the other 19th-century family wills I’ve worked with in its marked lack of detail. The only family member Christian mentions by name is his wife, my fourth great-grandmother Jane Ellen Doty Kegley (1819–1889). When he died on January 19, 1861, Christian owned 350 acres in White River and Union Townships (55% of a section or square mile, outstripping the land owned by my other Johnson County ancestors at the height of their holdings: in 1866, the Magills owned 332 acres and the Vaughts owned 240). Of these 350 acres, 190 contiguous acres of her choosing were to be Jane’s portion, while a further 44 acres (1/8 of the total) were to be divided more or less equally between Christian and Jane’s surviving children, of whom there were eight in 1861: Dr. John Lewis Kegley (1840–1907, my third great-grandfather), aged 20; Martha M. Kegley Cagley (1842–1931), aged 18; Christian Edward Kegley (1845–1933), aged 15; Fernando C. Kegley (1846–1925), aged ca. 14; Sarah J. Kegley Sandefur (1851–1877), aged 9; Thurza E. Kegley Surface (1853–1901), aged 7; Thomas H. Kegley (1857–1931), aged 4; and Florida “Flora” Kegley Groseclose (or Grose, 1859–1943), aged 1 (nearly 2). Thus, each child would inherit 1/64 of Christian’s land, or about 5.5 acres each. That seems an unusually small amount of land for a bequest: while more than large enough to build a house on, it does not seem enough for a profitable working farm (perhaps Christian anticipated the children would sell off their plots). The will delegates the precise details to three executors (“three disinterested free holders of the neighborhood”), two chosen by Jane Kegley and one “by the child at the age of twenty one years.” Thus, each child would receive his or her sliver of land on turning 21 (the oldest, John Lewis Kegley, would turn 21 on March 1, 1861, six weeks after his father’s death; the youngest, Flora Kegley Groseclose, not until 1880). I would love to know how this twenty-year process played out: Were the 44 acres divided up into 5.5-acre parcels as directed? Where were those parcels, exactly, and what ultimately happened to them? Did the Kegley children keep their plots or sell them off for the money? These are questions which may one day be answered by an exciting new acquisition at the Johnson County Museum of History: stacks and stacks of 19th-century property transfer books are now awaiting indexing and digitization. I can’t wait to dig into them on my next visit to the JCMH!

The remaining 116 acres and all Christian’s money and personal effects were left to Jane Kegley, the land to be liquidated at her discretion “to enable her to support and educate” Christian’s “senior heirs” and “for the support of my minor heirs if my personal estate should be insufficient.” The 116 acres seem to have been sold off eventually, but Jane kept a great deal of her personal portion: in 1880, nine years before her death, she still owned 130 acres of her original 190 (contiguous with her son John L. Kegley’s 60-acre farm).

Two witnesses signed Christian’s will on May 11, 1860: Peter F. Doty (1800–74) was Christian’s brother-in-law, Jane Kegley’s older brother. Peter’s farm was next door to the Kegleys’ in White River Township. Of the other witness, John Fullen, who actually vouched for the will in probate court, I have not yet been able to learn much.

A note about spelling: there is a bewildering number of variant spellings of the name Kegley. From the original German Keckel, Kockel, or Goeckel (that is, Göckel), later Anglicized permutations include Kockhle, Kockhlen, Geckley, Gockle, Cagle, Cagley, Caigly, Caigley, Kegley, Keckly, and Koegley. This will, for instance, vacillates randomly between “Caigly” and “Caigley.” By the end of the 19th century, our branch of the family had more or less settled on “Kegley,” while our cousins, the descendants of Christian’s uncle Johannes C. (the first of the family to migrate from Wythe County, Virginia, to Johnson County, Indiana, in 1823) settled on “Cagley.” There are a number of clues that “Kegley” and “Cagley” were pronounced identically in the 19th century, with a “long A” in the first syllable, both rhyming with “vaguely” (i.e., the first syllable rhymed with “vague” and not with either “egg” or “bag”): for one thing, this is how both names are still very often pronounced to this day! In modern-day Johnson County, the first syllable of Kegley may be heard as either rhyming with “vague” or “egg,” but the “vague” pronunciation is undoubtedly the older one. Recordings of the speech of my third great-uncle Clarence (1909–92), for example, reveal that the “egg” and “plague” vowels often fell together in the earlier local dialect: Clarence pronounced “bell” the same as “bale” (rhyming with “tale”). That Cagley still rhymes with “vaguely” was brought home to me not long ago as I was listening to Chicago talk radio in the car: local semi-celebrity Mike Cagley was announced as the host of an area sports show, and I actually heard his name as “Kegley.” When I Googled his name, I realized that he uses our distant cousins’ spelling. Then it dawned on me that both Kegley and Cagley have always been pronounced the same. The early spellings Caigley and Caigly confirm the notion that the first syllable originally rhymed with “vague” and not with “egg.”

In the transcripts that follow, I have used the original spelling wherever possible, with punctuation added only for clarity. Unusual or non-standard spellings are included without comment except when extra clarity is needed.

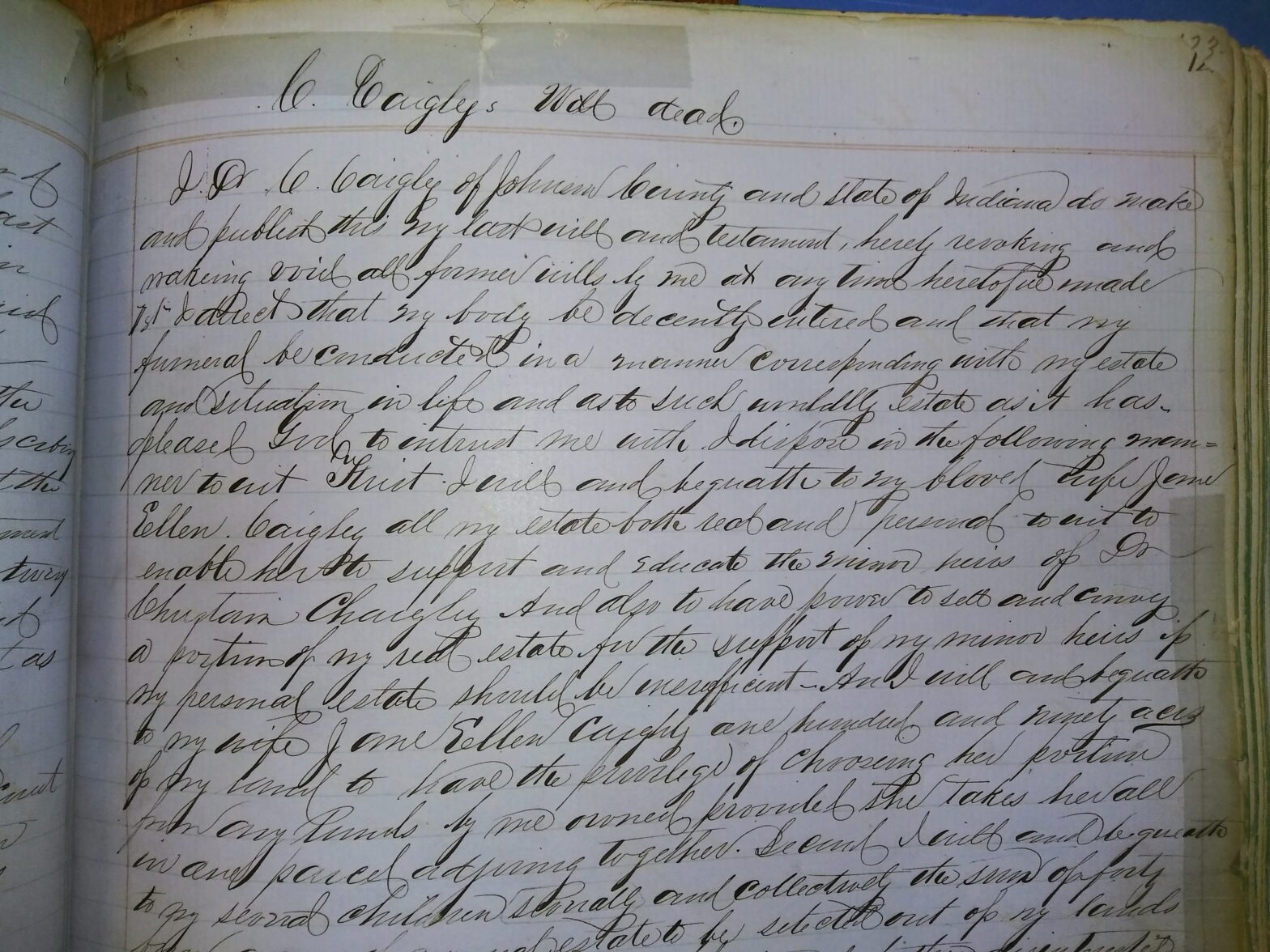

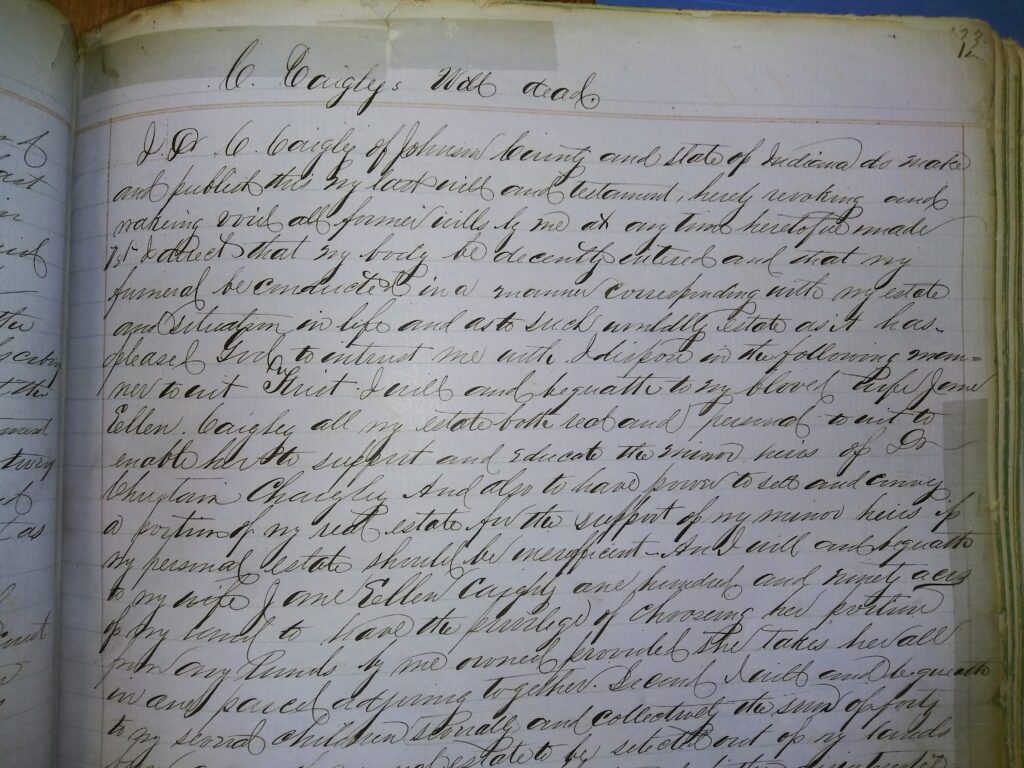

The Will of Dr. Christian Lewis Kegley (1803–1861), May 11, 1860, in a Probate Copy of January 31, 1861, Followed by Posthumous Attestation1

[Page 1 (121)]

C. Caigly’s Will Dead [“Deed”]

I Dr. C. Caigly of Johnson County and state of Indiana do make and publish this my last will and testament, hereby revoking and makeing void all former wills by me at any time heretofore made. 1st I direct that my body be decently intered and that my funeral be conducted in a manner corresponding with my estate and situation in life and as to such worldly estate as it has pleased God to intrust me with. I dispose in the following manner, to wit, First I will and bequeath to my bloved wife Jane Ellen Caigley all my estate both real and personal, to wit, to enable her to support and educate the senior heirs of Dr. Christian Chaigley [sic] And also to have power to sett and convey a portion of my real estate for the support of my minor heirs if my personal estate should be insufficient. And I will and bequeath to my wife Jane Ellen Caigley one hundred and ninety acres of my land to have the privilege of choosing her portion from and lands by me owned provided she takes her all in one parcel adjoining together. Second I will and bequeath to my several children severally and collectively the sum of forty four acres of my real estate to be selected out of my lands by me owned. The land to be apportioned by three disinterested free holders of the neighborhood to be selected as follows, to wit, two by my wife Jane Ellen Caigley and the third man by the child at the age of twenty one years. Then after being duly sworn by some person authorized to administrate [?] oaths shall proceed to set off the part or parcel of land that is allotted to each of my several children to, wit, forty four acres or so much as will make an average amount to each child provided it over runs forty four acres or falls short, to wit, so it maks the average amount which is one eight of three hundred and fifty two acres of land, part in Union Township and White River Township, Johnson County, Indiana. In witness whereof I set my hand this May 11th, A.D. 1860. Dr. C. Caigly, signed, sealed, published, and declared by the undersigned testator.

Dr. C. Caigley

Witnesses

John Fullen

Peter Doty

State of Indiana, Johnson County ss.2

Be it remembered that on the 31st day January 1861, John Fullen, one of the subscribing witnesses to the within and foregoing last will and testament of Christian Caigley, late of said county deceased, personally appeared before the Clark of the Courts of Common Pleas of Johnson County in the

[Page 2 (122)]

Dr. C. Caigly’s Will deed

State of Indiana, and being duly sworn by the clerk of said court upon his oath declared and testified as follows, that to say, that on the eighteenth day of August 1860, he saw the said Christian Caigly sign his name to said instrument in writing to be his last will and testament, and that the said instrument in writing was at the same time at the request of the said Christian Caigley and with his consent, attested and subscribed by the said John Fullen in the presence of the said testator and in the presence of each other as subscribing witness thereto, and that the said Christian Caigley was at the time of the signing and subscribing of the said instrument in writing as aforesaid pf full age, that is, more than twenty-one years of age and of sound and disposing mind and memory and not under any coercion or restraint as the said deponent verily blieves, and further deponent says not. Sworn to and subscribed by the said John Fullen before me W. H. Barnett clk of said court at Franklin the 31st day of January 1861, on attestation whereof I have hereto subscribed my name and affixed the seal of said court. W. H. Barnett clk

State of Indiana

Johnson County ss3

I, W. H. Barnett, Clerk of the Court of Common Pleas of Johnson County, Indiana, do hereby certify that, that [sic] the within annexed last will and testament of Christian Caigly has been duly admitted to probate and duly proved by the testimony of John Fullen, one of the subscribing witnesses thereto, that a complete record of said will and the testimony of the said testator in proof thereof has been by me duly made and recorded in Book A. at Pages 121 and 122 of the Record of Wills of said county. In attestation whereof I have hereunto subscribed my name and affixed the seal of said court at Franklin this 31 day of Jany 1861, W. H. Barnett Clerk C. C. P. J. C.

- From Will Record Book 2 (Aug. 1852 – Nov. 1878), Johnson County Museum of History, p. 121–22 (digital pages 143–44 https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-XQF6-X963-3?view=explore&groupId=TH-7786-121639-141-63). ↩︎

- This is an abbreviation for Latin scilicet, meaning “namely, in particular, that is to say.” It is often used in the venue section of legal documents—the part that specifies the state and county where the signer appeared before the certifying or notarizing official. See https://www.quora.com/In-legal-documents-what-does-ss-stand-for,

https://www.notarypublicstamps.com/articles/the-importance-of-the-venue-on-a-notarized-document/. ↩︎ - See previous footnote. ↩︎